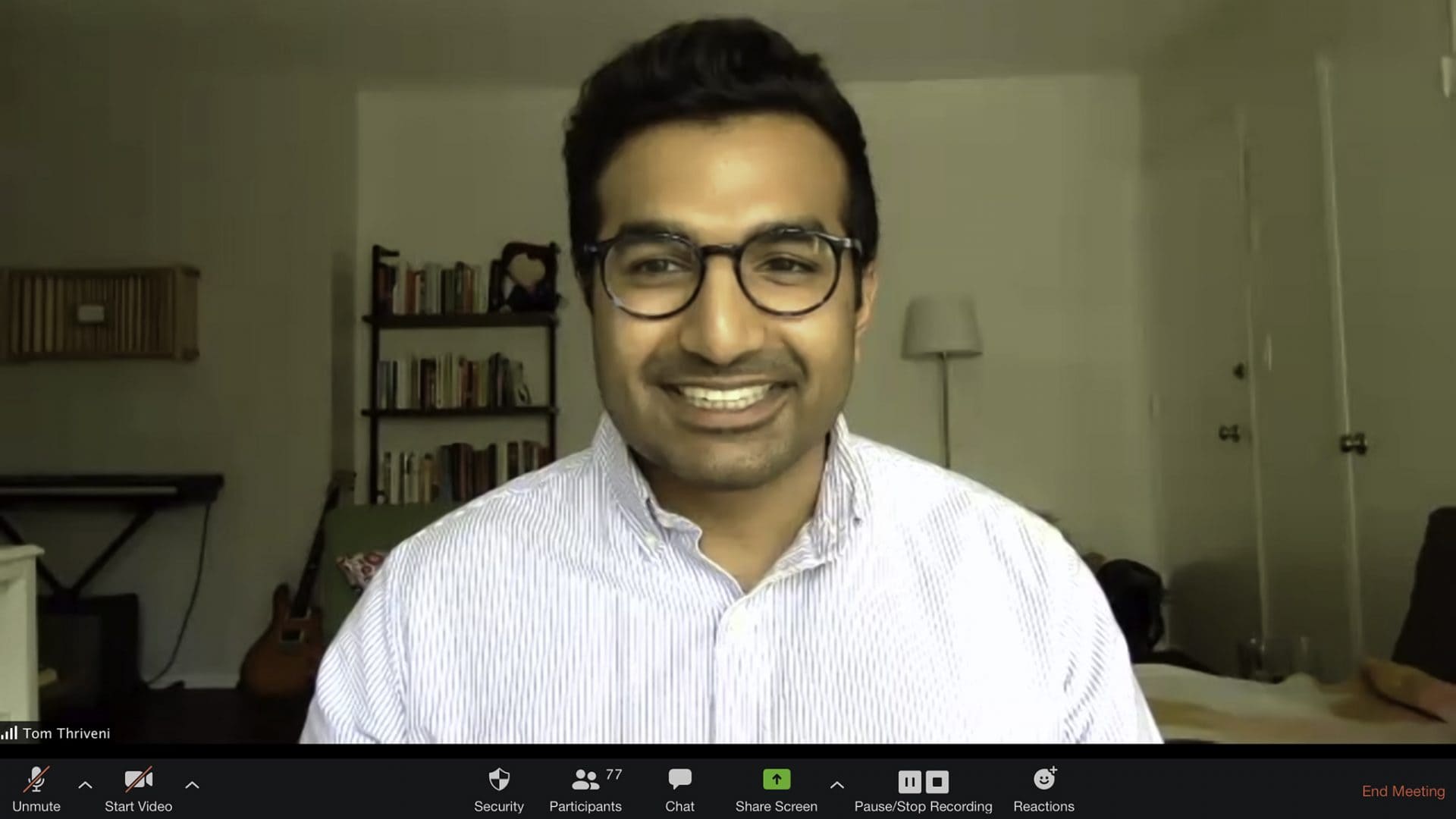

Tom Thriveni ’10, staff writer for The Late Late Show with James Corden during last week’s Virtual SEVEN Speaker Series event on May 6, 2020.

A Vital Lesson Well Learned. I experienced the most amazing Zoom session Wednesday night as a viewer. The people who made college possible for me, the prestigious Morehead-Cain Foundation, has a network of former and present scholars around the world in every sort of profession and job (Frank Bruni of the New York Times, Alan Murray who runs Fortune and Time, Inc, our current and great North Carolina governor, the best selling novelist Shilpi Somaya Gowda, British television producer James Dean, and on and on). All are graduates of UNC Chapel Hill and keep in touch across space and time in various ways.

This week’s evening event was the second in a series of group Zoom sessions (I sadly had to miss the first) where our Morehead-Cain “cousins” – as we call each other – will variously speak on topics from our own lives. Last night, our speaker was Tom Thriveni, the accomplished Writer for The Late Late Show with James Corden (that super talented dude who also rides around and does Carpool Karaoke with top vocalists like Adele). Tom spent the hour talking about his life journey and how he learned self-trust, which is a big challenge for a lot of us, regardless of where we are in life. It was one of my favorite chats ever.

Tom’s parents came to America from India and worked hard to create a good life for their children, whom they hoped would get great educations and go into solid professions where their futures would be assured and they wouldn’t have to take the sorts of risks their parents had embraced in order to begin a new life here. Tom was on track. Great university. Econ major. But then a wild summer internship with Jon Stewart on The Daily Show sparked a flame. And he knew what he wanted to do. But it was too risky. So he became an investment banker instead and then went into private equity as impressive stepping stones to eventually attending Harvard Business School and then of course ruling the world from a corner office high up in a tall building somewhere in the world, and thereby making his parents both proud and unworried for his future. But investment banking and private equity weren’t for him. The pressure, the long hours, and the not at all loving the work put him in the hospital for brain surgery. Yeah. More than the normal work headache. Brain surgery. Maybe two of the scariest words in English. It went well. So he became a comedy writer. Obviously. The surgeons removed all the grey cell investment banker-equity neurons and his remaining synapses naturally reverted to jokes.

“Mom. Dad. I have news.” Oh, no. The conversation. The previous such chat, involving cranial cutting as it did, wasn’t a great precedent. How not to end up back in the hospital? How could he face this? But back up. How could he face the world of comedy, which of course is not known for any guarantees concerning corner offices in tall buildings, world power, and impressive wealth. But Tom had developed a trick. Whenever he confronts a daunting new possibility, something he really wants to do but that has a failure rate percentage with numbers that better reflect normal body temperature, nowadays around 98.3% or something, he uses his imagination. He’ll ask himself “What’s the worst that can happen?” And in pretty much every case where he has ever employed the question (apart, of course, from the brain surgery), the answer has been a version of: “I’ll do something very interesting and fail and come away with some great stories to tell.”

And he has learned something else along the way. Great people make what they do look easy and natural. But whenever we tackle something big and new to us, it doesn’t typically feel easy or particularly natural in the early stages. And so people give up. Tom figured out that something’s being really hard at first doesn’t mean that you’re not supposed to do it, or that you’re not meant to do it, or that it’s not for you. This is exactly what anything challenging and interesting is supposed to feel like at first. That “natural” free throw shooter? Yeah, he makes it look easy after those three million practice shots we never saw.

Tom also learned a third thing. As if these two aren’t enough for that corner office, at least metaphorically speaking. Because, yeah, in comedy you learn to work with metaphor. It beats brain surgery. At least on one end of the surgical scenario. He learned that success isn’t about big titles, major status, and great sounding attainments. He said something profound: “The process is the joy.” And that’s a powerful secret.

The joy isn’t in being named “Writer” for a major television show and being known for the signature monologues that make America, and often the world, laugh. It’s about the process. But then when he described his normal day and what the process is like, I could see that, first, it’s a good thing he’s a lot younger than me to work the hours he does, and second that to enjoy a process that hard is living proof he’s found his thing. Nothing makes it easy. But the fit with his passion makes it great.

Thanks, Tom Thriveni, Writer, Great Zoomer, and Philosopher of Life!

Tom Morris is a philosopher, public speaker, and author. You can read more of his work on his website.