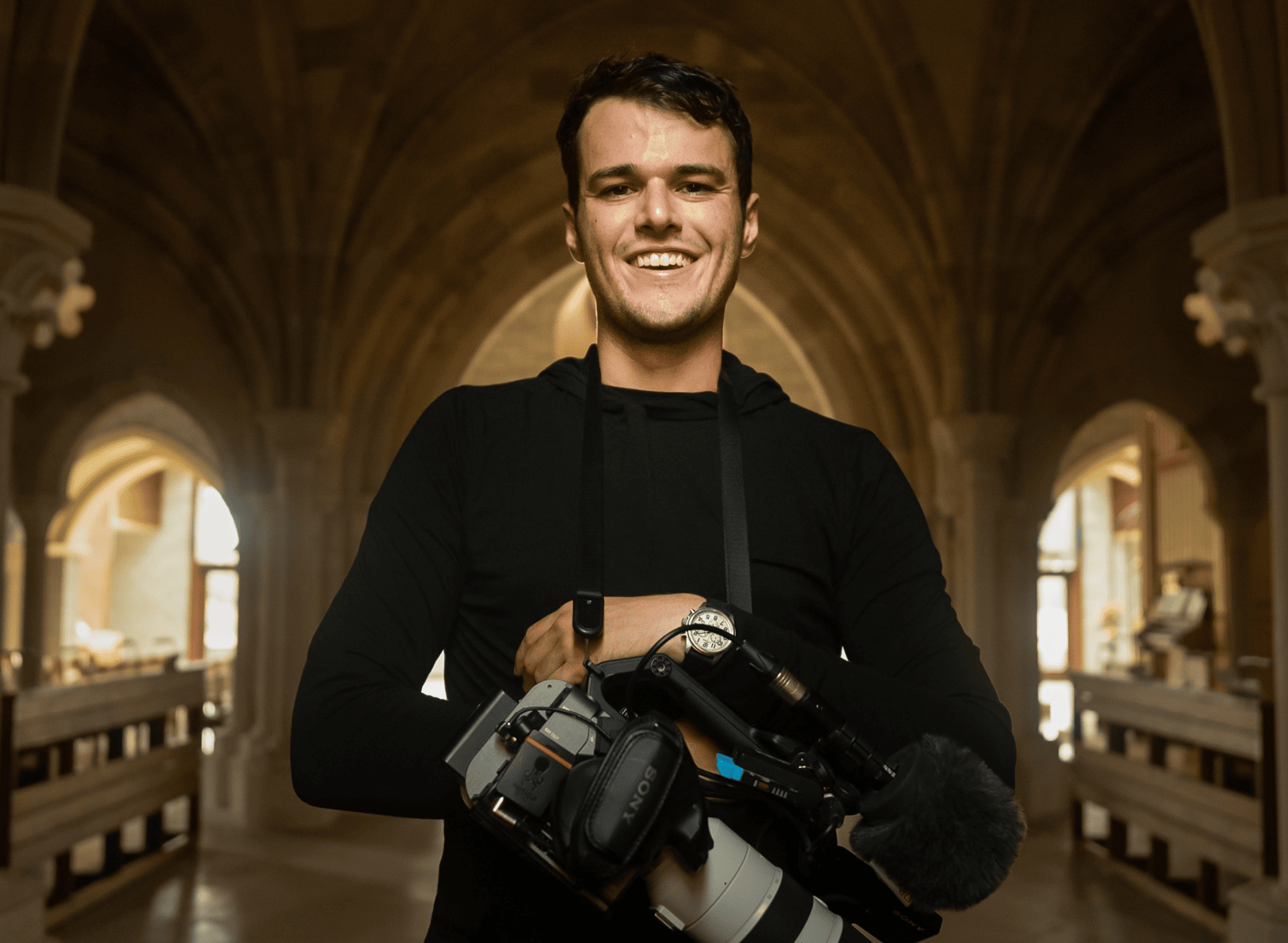

Rob Gourley ’18 is based in Chico, California.

Rob Gourley ’18 is a documentary producer, cinematographer, and video editor based in Chico, California. During the pandemic, the alumnus was working for the Los Angeles Times as a video producer when an opportunity came up to work for PBS on a NOVA series about electric airplanes. What was intended to be a sabbatical turned into the launch of Rob’s career into freelance.

Rob shares with Catalyze about his decision to take a big risk, his aspirations to make a documentary about wildfires, and how he became one of the first videographers for the show Doug to the Rescue.

Music credits

This episode features songs by Scott Hallyburton ’22, guitarist of the band South of the Soul, and Nicholas Byrne ’19 of Arts + Crafts.

How to listen

On your mobile device, you can listen and subscribe to Catalyze on Apple Podcasts or Spotify. For any other podcast app, you can find the show using our RSS feed.

Catalyze is hosted and produced by Sarah O’Carroll for the Morehead-Cain Foundation, home of the first merit scholarship program in the United States and located at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. You can let us know what you thought of the episode by finding us on social media @moreheadcain or you can email us at communications@moreheadcain.org.

Episode Transcription

(Sarah)

Rob, thanks so much for speaking with me today.

(Rob)

Hi, Sarah. Thank you so much for having me on.

(Sarah)

The last time I checked, you were a video producer for the L.A. Times. Can you share about that experience and what inspired you to take the leap into freelance?

(Rob)

It was a really foundational experience for me. Every day, I was constantly hopping between a lot of different projects that demanded a lot of different styles. Some of the projects were a little more cut-and-dry journalism pieces but others allowed me to—they were still journalism but were more feature-oriented—allowed me to bring a little bit more of a vision to it and a little bit more creativity to telling the story.

The longer that I was there, I realized that the projects that I looked to the most for inspiration, and the projects that I most wanted to create eventually in my career, those weren’t necessarily being done by people who were working at newspapers or at journalism outlets, necessarily. They were produced by, in large part, people who are freelancers.

One of the things that I started to see once I got into the industry was that even the longer-form documentary stories that are produced at newspapers are generally made by partnerships between newspapers and independent filmmakers or newspapers and video-centric video production companies.

Obviously, the work that video journalists do is incredibly important, and there’s a need for that, but the niche that it fills wasn’t necessarily where I saw myself going long term.

I also wanted a little bit more ownership over my work. I started thinking about freelance earlier on, and then the question was when to make the jump. It’s been a wild time to become a small business owner, but I’m really fortunate to have been able to make it work so far.

(Sarah)

I mean, to make that kind of decision in the middle of the pandemic must have been probably a little scary? Or was it mostly just optimistic because you knew that the time was right to do something for yourself?

(Rob)

It was definitely really scary. Initially, I didn’t anticipate making that jump. During the pandemic, I’d been thinking about it a little bit off and on. It was just luck and happenstance that I ended up having an opportunity to actually, for a moment, step outside the paper and work on an external project.

I was contacted by a production company that I had actually interned with in my time at Carolina. It was one of my Morehead-Cain SEP summers.

(Sarah)

Miles O’Brien Productions?

(Rob)

Yeah, Miles O’Brien is the science correspondent for the PBS NewsHour, and he runs a production company. It used to be out of Boston when I interned with them. They produce a lot of science-focused content, and that’s a bit of my forte. I really like that kind of content. I had a chance to intern with him in college and had just kept that connection alive and kept reaching out and talking with my friends there.

They were looking at doing a NOVA documentary about electric airplanes, and it just so happens that a lot of the companies who are doing that kind of work are in California. They needed someone out here to do a lot of the filming for it and work on shoots to fulfill a lot of roles, including audio and lighting and filming. They reached out while I was at the paper and they said, “Would you be available to do this and join us for a couple of weeks of filming here and there?”

This is something that I was really interested in, and obviously, it’s a PBS Nova film. It’s an incredible opportunity to work on something like that. So, I ended up requesting to take a sabbatical from the paper to work on this project. What started as a sabbatical turned into a resignation and going freelance full time.

I was really lucky to have a chance to just take a step out of that door in a safe way. I could come back to the job—that was my plan at the start of it. But I think once I took that step out, I saw that for me at least, the grass really was greener. It’s not without its own drawbacks, but just having a chance to step into the freelance world and work on a project that’s in the style that I really wanted to be working on (longer-form documentary storytelling) made me realize that it was doable in the moment. And yeah, I made the jump.

(Sarah)

What are you curious about pursuing now? Are you thinking about any specific issues that you want to tackle or do you even have a specific documentary in mind that, if you had the time and resources to do it, you’d want to pursue?

(Rob)

Some of the stuff that I’m most interested in working on are stories that are really immersive for audiences. What I mean by that is when people generally think of documentaries, a lot of the time when you watch a documentary on TV or even on a streaming service, there’s generally a lot of information. That’s the typical model. There’s a lot of information, usually a narrator or reporter leading someone through a story. It’s packed with a lot of statistics and relevant information.

Those documentaries have their place, and they’re really important but I also see this need for documentaries that can really pull someone into someone else’s experience and maybe convey information and emotion using some of the same language that’s not really used in documentaries, but maybe more so used in cinema.

When you go in and you watch a film in a movie theater, you generally expect something or you expect a very different experience than watching a documentary. The fundamental language that’s used between the two genres, generally, can differ a lot, it can differ a little, but there are more and more films coming out that are exploring the style called cinéma vérité.

This style has been around for a while. Honeyland would be a great example of a recent, well-known film that’s in pursuit of that style, of really immersing an audience member in someone else’s experience and using that as a means to convey meaning, to convey information.

In terms of looking at the environment. It’s hard to find stories that do that. When you’re talking about climate change, for example, something that often comes to mind is glaciers melting. While that’s horrific that’s taking place, for the average person, it’s hard to see how that connects into daily life. It’s hard to watch clips of animals in the Arctic or these processes that are slow enough that it’s hard to convey on screen. These processes are taking place, and it’s just hard to really get these things to really hit home with many people in the audience just because it’s hard to relate to these things. These things are abstract. They happen over longer periods of time. They’re not really in your day-to-day life.

For me, an area that I’m increasingly interested in focusing on that deals with that is wildfires. I had a chance to cover a couple of wildfires while I was at the Los Angeles Times. The experience of being in that environment, with the fire raging around you, it’s one of the most visceral, immediate examples that I could think of off the top of my head that really shows the impending crisis that we’re all starting to go through now, and that we will be experiencing in the next ten, twenty, thirty years.

(Sarah)

There is something so pressing about actually looking out your window and seeing an orange haze because a fire is just miles away in that it doesn’t feel so distanced, like a glacier melting, which few of us will probably get to go see, but something that’s a bit more day-to-day and in your face.

(Rob)

Absolutely. Especially for people who are out on the West Coast. Last year, we had a really awful set of fire complexes in Northern California, where in San Francisco, the sky was orange. Here where I live, in Chico, out in rural California, there was a day where it rained ash, and the fires weren’t even at our doorstep. But it clouds the air. There’s like a haze whenever there are fires about, and it almost seeps into every aspect of life.

I think, granted, someone on the East Coast, or people who live in areas that aren’t as prone to fire, probably can’t share that experience. But just knowing that there’s this intersection of this intense, visceral fire and people coming together, there’s like this intersection there that’s really intense and immediate. There are stories that take place all around that, from preparing to during to after, the healing process. There’s so much there that’s relatable and immediate and visceral, and that has the power to be immersive. So, focusing on stories like that is something that I’m really interested in working on in the future. I also have a little bit of this wild idea for how to film it, too.

(Sarah)

Tell me about this.

(Rob)

If anyone had a chance to see 1917 this past year, year and a half, it came out. It’s filmed by one of my favorite directors of photography, Roger Deakins, and it was presented as if the whole entire movie was shot in one single take. There’s no cuts. There’s no different shots. It is shot as if it’s just the camera moving through the landscape, following the characters, and it’s by no means the first movie to do this.

There’s a lot of theory behind this, and I could talk at length about why it works this way but when you’re presenting a film to an audience that contains such intense subject matter, and you don’t include any breaks or any cuts for them to be able to really even blink, it just becomes so immersive and so much more intense. It really doesn’t even give the audience a chance to really even look away or catch a breath. It’s really almost relentless, in a sense, even though there’s no fast cuts, it’s just like one long take.

I’ve been trying to look into it, and there are reasons for this, but there aren’t any documentaries that really take place in one cut, that’s really moving through a landscape that develops characters, and that takes you through a story in that way. I’ve been thinking about the intensity of wildfires and really trying to immerse an audience in the human experience around that to really convey what’s going on. I’ve been thinking about the idea of trying to do it in maybe even one take or several really long takes.

The work that would have to go into that is fairly immense. It’s not as easy as just like going out and just filming for an hour with a camera. It would take a lot of prep work, and it would probably take a lot of tries before getting the right take. But the thought of trying to create a really immersive documentary in that way is really interesting to me, and that’s something that’s pie in the sky that I’m dreaming about. Maybe I’ll have a chance to make the documentary at some point.

(Sarah)

You’re also working on natural disasters with Doug to the Rescue, which I’d love to talk about next. Tell us where the idea for the show came from and why you got involved, why you wanted to get on board.

(Rob)

Yeah, so, back when I was working on the NOVA film during the sabbatical, and right after I went freelance, the other cinematographer that was working on that project had just pitched the show and got into proof of funding, and we started talking about it and it immediately caught my interest.

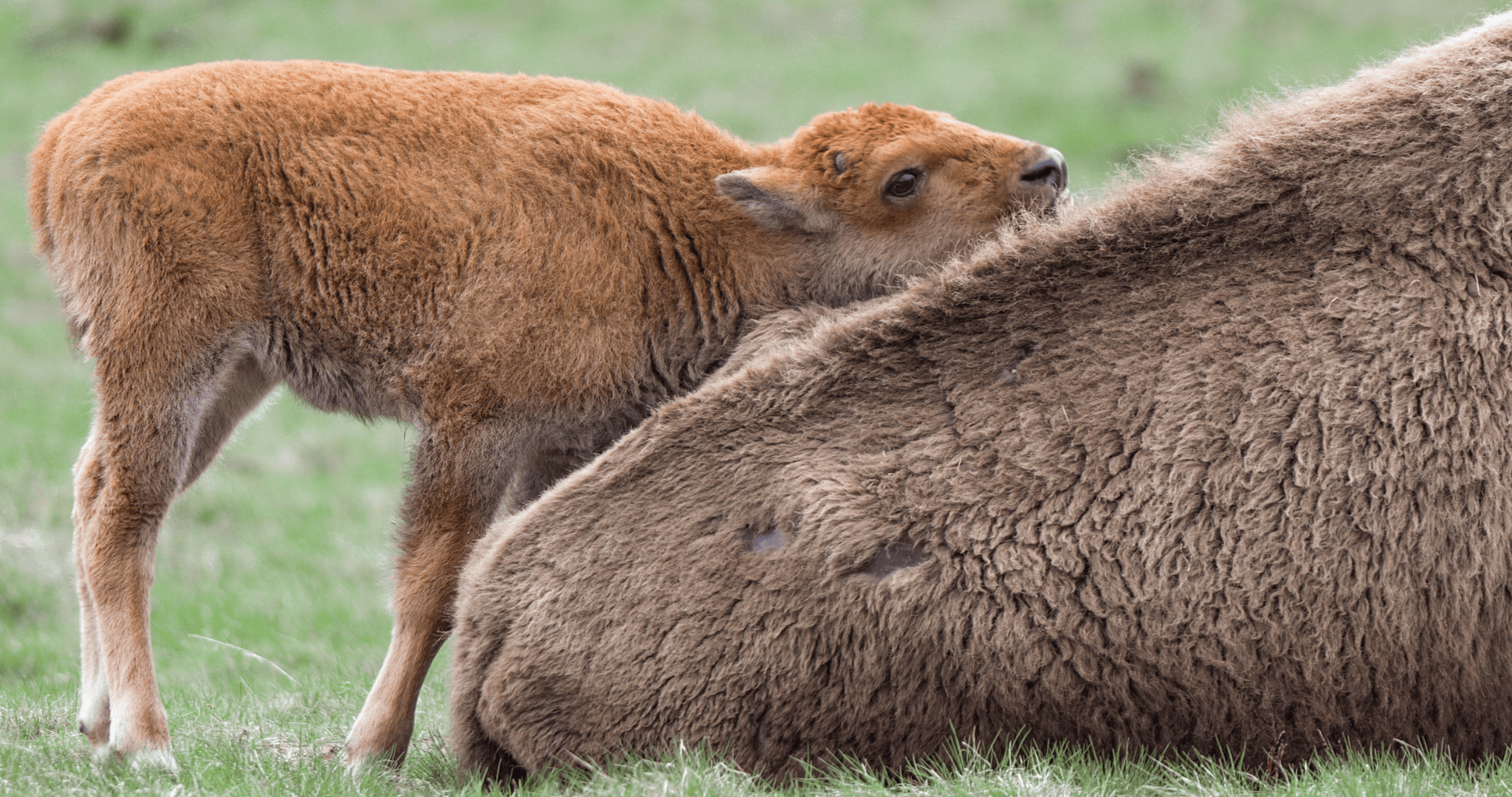

The show originated when this cinematographer was in the Bahamas after Hurricane Dorian. He was there doing more or less just general news coverage, and he ended up running into this guy named Doug, who was flying this really sophisticated drone for the purpose of rescuing animals that had been separated from their owners or that had been stranded after the storm, who are basically left helpless on their own.

He immediately befriended him. They started talking about the possibility of doing a bigger documentary project about Doug’s work just because it’s so interesting, and they were able to pre sell it through Curiosity Stream as one of their first original series.

The reason why it stood out to them was the same reason that I got really interested in it. There are a lot of animal rescue shows out there. That concept isn’t really new. But what makes Doug’s show so different is there’s this really interesting intersection of technology that really has only become commercially available in the past couple of years.

There’s a connection of that with all these environmental issues. He’s going in and rescuing animals after these events that are becoming more intense and more frequent because of climate change. Those topics are intersecting over this core mission of wanting to go and save the helpless, like rescue these helpless animals that, if left on their own, would perish.

So, it’s these interesting themes intersecting over a show that at its core has a lot of heart. It just so happened that the cinematographer who had pitched the show, who is an executive producer on the show, he was tied up in a lot of different projects that he had already committed himself to, and they needed people, at the spur of the moment, hop on these trips after natural disasters, which we couldn’t plan for. He said, “Would you be interested in working on this in a big way?”

Coming out of the project, he had seen a little bit of my work, and we had a chance to work together, and he got to know me that way. He felt comfortable enough and asked me to be a part of it. I was absolutely on board because at that point, too, I was so early in my freelance career, I had a lot of availability. It just really worked out.

The first shoot that I went on was in Louisiana after Hurricane Laura. It had devastated this small city called Lake Charles, and there’s a lot of news coverage about it. Doug was debating on whether or not to go. We were trying to make sure that things would work out on the ground.

Really at the core of it, this was so early in the production process, and this was the first season of the show. There wasn’t a formula or a template for determining whether or not certain locations or certain events would work out for us that Doug would have a lot of animals to rescue. Initially, it was a really small team that they sent to Louisiana, because in their minds, they were saying this might be a total wash. There was funding but it was the first season of the show. There wasn’t a huge budget for it.

Really, for most of the time there, it was just me, one other producer, and Doug. We were sent down for what initially, they said, like, maybe it’ll be a couple of days, we’ll feel it out and see from there. What initially might have been only a couple of days ended up turning into almost two weeks of really long filming. Because the show hadn’t been super established yet, there were some things that we talked about going into it, but because there was so much blank canvas to work with, I had an opportunity to really bring my own style and vision into the making of those episodes.

In Louisiana alone, we pulled out two episodes from that trip of the six. I was with them for other shoots, too, but that was the first time that I was on the project. I just felt so lucky to be working on a project that was going to be distributed, had funding like that, but also be able to really have the creative freedom to bring my own eye into it. I feel like that’s at a higher level, at a higher caliber. Those opportunities are a lot more rare.

(Sarah)

Yeah, well, especially after, as you said, you were hoping for more creative freedom at the Los Angeles Times, as wonderful as a first job that it was, and just less than a year later, essentially, to be working on this, is just really exciting. My last question is, what does the word “tequila” mean to you at a personal level?

(Rob)

On a personal level, Tequila is my dog. My partner and I ended up rescuing him off of the show, Doug to the Rescue, spur of the moment. But Tequila and I make an appearance on the show. I make a little cameo.

But backing up a little bit more. I grew up with dogs. I grew up with rescue animals. In my mind, I knew at some point that was going to happen. I was going to try to adopt the dog. I didn’t know when that would be, and I thought it would be a lot further down the road.

But when I hopped onto this show, you’re out there rescuing animals who are just so helpless. All they want to do is to have a home and to just love you and just to be loved. It’s one of the most pure expressions of love that I’ve ever experienced. Do you want me to go into the backstory of how we found him?

(Sarah)

Yes, please do.

(Rob)

So, it was late, really late at night in Louisiana. One of the quirks of the show is that, for the drone to work, it uses an infrared camera. It has to fly at night, so we would work long hours into the night. At three or four a.m., we were wrapping up. It had been a really, really tiring night. We had filmed a lot. We had picked up a lot of cats and dogs, and Doug and I were driving back to pick up the producer, who had been sitting with some of our equipment. Suddenly, as we’re driving, this dog walks through the beam light on the sidewalk.

Doug looked over at me and he said, “Should we rescue that dog?” In my mind, we were like, “Oh, we’re really tired. It’s really late. We don’t have a kennel for it.” But we decided to go for it. He wanted to do it since the dog was right there. We wanted to at least give it a shot.

Tequila was really skittish at first but clearly wanted to be friends. He had gone at least ten days scavenging for food and water on the street. He was really hungry, and we were able to eventually get him over and put a leash on him. It took a while to coax him in and get him into the car.

We didn’t have a kennel because we were working with a group there that had all that equipment, and they had already gone back to the shelter. The only option was for Tequila to sit in the back of the car with me. At that point, he didn’t have his name. But in my mind, this dog had just been through probably what was one of the worst experiences of its life, where it had been on the streets through a hurricane and then had to scavenge for food for ten days and find water.

After an experience like that, I would be really angry. But Tequila, riding all the way back to the shelter in the car, he just put his head on my shoulder, and he gave me a hug the whole way back. In that moment, it just became clear, like he went through all that ordeal and was just still at the end of the day, so loving and sweet and kind. It just broke my heart wide open. I don’t think I could not adopt it at that point.

(Sarah)

If only you knew at the time of leaving your job that, not only would you be working on this cool project, but you’d also have a new addition to the family.

(Rob)

Yeah, who knew?

(Sarah)

Rob, thank you so much. I really appreciate it. Best of luck with all of your projects, right now and the ones to come.

(Rob)

Thank you so much, Sarah. Take care.