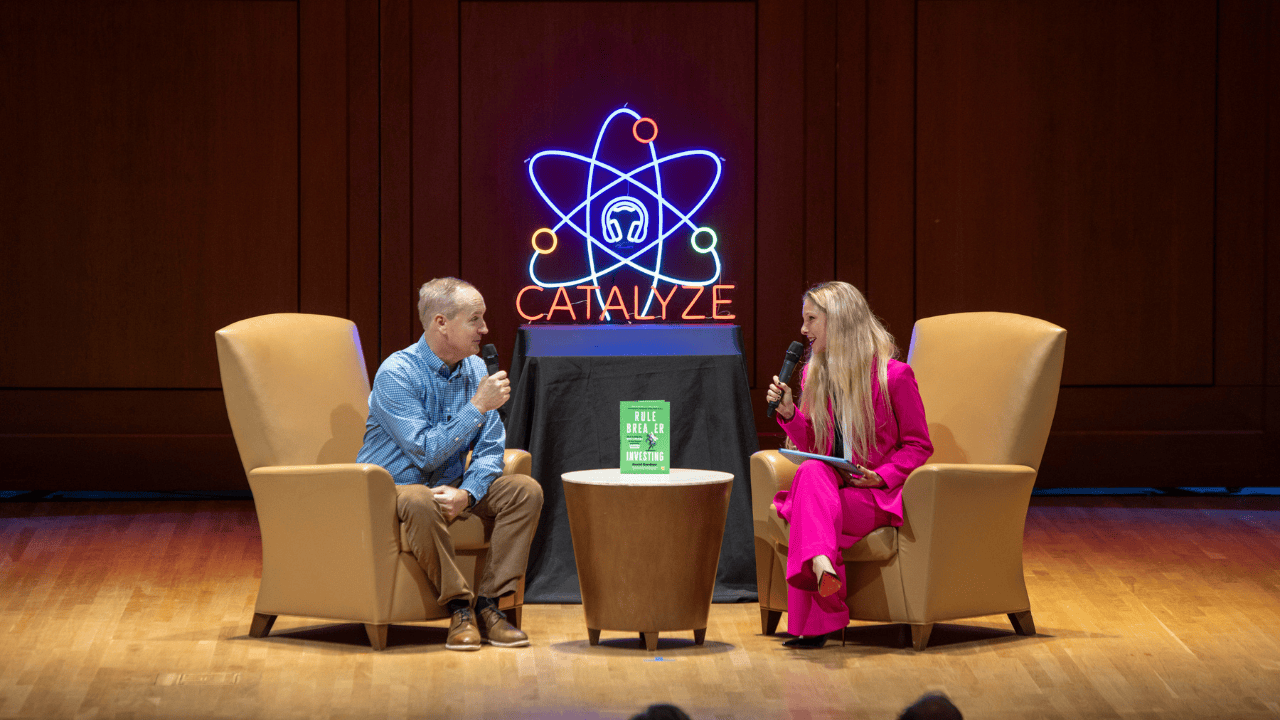

David Gardner ’88 and Mary Esposito ’26 (photo by Leon Godwin)

Recorded live at the 2025 Morehead-Cain Alumni Forum, this episode of Catalyze brings together two generations of financial innovators. David Gardner ’88, co-founder and Chief Rule Breaker at The Motley Fool, shares decades of experience challenging conventional finance: what worked, what didn’t, and the lessons he’d carry forward.

This episode’s host, Mary Esposito ’26, is the founder of Money with Mary. The financial literacy initiative is designed to make personal finance approachable and empowering for Gen Z.

How to listen

On your mobile device, you can listen and subscribe to Catalyze on Apple Podcasts or Spotify. For any other podcast app, you can find the show using our RSS feed. You can let us know what you thought of the episode by finding us on social media @moreheadcain or you can email us at communications@moreheadcain.org.

Episode Transcription

(Mary)

Hey, y’all. Welcome to—I’m Mary Esposito from the Class of 2026, and this is David Gardner from the Class of ‘88. We’re here at the 2025 Alumni Forum in Chapel Hill, and this is our very first live recording of Catalyze.

(David)

I’m so excited to be here with Mary Esposito.

(Mary)

David, thank you so much for being here.

(David)

It is my delight.

(Mary)

How many Alumni Forums is this for you?

(David)

I think this is eight. I think there have been nine, and I was definitely there for the first. I missed one. It’s such a special time once every three years. And so, to be here and see so many people—700-plus for the first time—the largest, Chris Bradford, the largest gathering ever of Morehead-Cain Scholars in one place. So special. Number eight.

(Mary)

I could not agree more. This is actually my first one, so I’m super excited and grateful to be here. So today we’re investing in something a little different: the wisdom you’ve built over three decades of breaking the rules. From co-founding The Motley Fool to reshaping how millions think about investing, your story is all about risk, rule-breaking, and lessons learned. For y’all, you can think of this conversation as a diversified portfolio: some origin stories, a few bold bets, and long-term returns, of course. So, without further ado, let’s dive in. David, you studied English and creative writing at UNC Chapel Hill during your time here. When did you first realize you had a tendency to break the rules? And was it during your time as a Morehead-Cain Scholar?

(David)

Thank you, Mary. You prepped me a little bit, so I was ready for this question, and I’m glad I was because I needed to think about when was the first time that I really broke the rules. I think I can say with certainty now that it was accepting a Morehead-Cain scholarship. That really was, for me—and I think many people hearing us right now—that was the road less traveled. I wouldn’t say it was a risk. It was just mainly an amazing opportunity, but it was not what I was expecting to do junior year of high school at St. Mark’s School in Southborough, Massachusetts. I’d applied early to Yale. I was excited about drama. I wasn’t thinking about the stock market, and I was thinking about New England. And then, all of a sudden, I got to come down to finalist weekend somewhere in March in Chapel Hill from frigid Southborough, Massachusetts, and everything changed. But really, that decision to go a totally different direction was definitely breaking the rules for me, and I think it’s shared by a lot of people in the room.

(Mary)

I can totally agree. I am in the inaugural cohort of the sophomore selection program, so it’s also new for me, too, and I did not plan to be here, but I could not be happier. So, I’m so glad we have that in common.

(David)

One rule breaker to another, Mary. It’s true. And I really love that there’s the sophomore intake. I love that new innovation that Chris has brought to this program. And you’re a living example of people who show up freshman year and are awesome. And I want to say we won’t talk about this, but I was pretty much not awesome my freshman year at UNC Chapel Hill. So, it was the people who were awesome that really should have gotten—and now are getting—the scholarship.

(Mary)

It sounds like these early lessons really set the stage. Let’s now talk about when the stakes were a little higher and the risks were a little more real. In 1993, you and your brother Tom co-founded The Motley Fool, which originally started as a newsletter. That was a pretty radical move at the time. What was that leap like—stepping away from the safe path to start something brand new?

(David)

Well, I was writing for Louis Rukeyser. Older folks in the room will recognize him as the longtime host of Wall Street Week on CBS, a long-running show. I was writing for the financial newsletter, and all of a sudden, I realized this is not a good job. It’s my first and only job. I was only three months in, and I started going, “I’m writing the back page of this financial newsletter, and I could pick any topic I wanted.” So, let’s say discount brokers, which back in 1992 were a brand-new thing. We could try Schwab and pay less to buy a stock than Merrill Lynch. And so, I’d write that, and my article would come back edited. And the first half was an abridgment of what I’d written, with any color, any fun, any pizazz, any humor—gone. And the second half was all the reasons that you wouldn’t want to do discount brokers or Quicken, for those who remember back when Quicken showed up, and we all of a sudden could track our expenses on our computer. So, I would pick things that I thought were helpful, and then I would have this really boring article that came out, and I met with Sula, who was my editor between me and Rukeyser, and she said, “Well, Mr. Rukeyser’s portion is the color. It’s the fun. Our part needs to contrast with that.” I was thinking, “We want to contrast with fun and color?” Somewhere around month four, I said, “I think I’m going to step away.” They said, “Stay on two more months.” There I was, in my mid-20s, the only job I’d ever had, I had not held down for six months. My college career was unexceptional. I love being here. I loved my summers. So, at that point, I think all I really could do was start a paper newsletter for our parents’ friends—the only ones who would pay us $48 a year—for our thoughts. And that launched The Motley Fool.

(Mary)

That’s incredible. I’ve been following you all for a long time. I actually use The Motley Fool, and I have been since I knew that you were a Morehead-Cain alum, which is super crazy. I have a question. So, you’re known for investing in Amazon early and giving it as a good stock pick and holding it through the ups and downs. Do you credit those wins more to patience, preparation, or when others doubted?

(David)

I think, first of all, there are two things for any great investment: getting in and then staying in. And those are different things. So, I’ll speak to both briefly. I think that finding a company like Amazon, NVIDIA, Tesla, or Netflix—the list goes on of some of the great companies of our time, the innovators—these are all different industries doing completely different things. But they shared patterns that I started to realize, Mary, were helpful to realize which stocks are going to end up being big winners. I think we’ll rattle through those in a little bit, so I won’t say that now. But I’ll just say pattern recognition around what’s going to win and then getting in—not as early as the venture capital crowd, which is well represented in this room today. I wish I could get your cost bases, but unfortunately, I have to wait for companies to go public before I can recommend them as stocks. But getting in as early as we can is great. That’s step one. Step two, Mary and everybody else, is, of course, holding. And for that Amazon investment, our original cost was $3, and it went to $95 after five years.

(David)

And then 2001 happened, and it went from $95 back down to $7. There were a lot of Motley Fool members who loved us, loved that stock, and we watched it go from $95 back down to $7. And that hurts. That hurts a lot. And that’s not the only time that Amazon, Tesla, Netflix, or NVIDIA have made death-defying drops of 50 percent or more. In fact, it’s going to happen several times anytime you find even the greatest companies if you look to hold them for 20 or more years, which is what we typically do. And I think that patience part—the word you used—is something that is a virtue that few hold. And I think we live in a world where people are jumping in and jumping out of stocks. Even at the institutional level, the professionals often don’t own on December 31 what they started with on January 1 of that same year. And so, I think it’s a two-step process.

(Mary)

I could not agree more. I know how you feel about the dropping. I’ve been holding Palantir for a couple of years. I also have a more long-term investment strategy as well because I’m trying to retire super nice and super early.

(David)

Well, we all want that for Mary, am I right? More fun, right?

(Mary)

I can move back in with my parents and spend tons of time with them. Right there.

(David)

I mean, Palantir has been a monster winner. It is a stock that we have in our portfolio—not because of me, but because of my fellow Morehead classmate and lovely wife, Margaret, who said to me about a year and a half ago, “What about Palantir?” And I thought, “You’re right.” And it has been a fantastic company, and it is volatile. And that’s part of what you’re recognizing. Rule breakers by nature—the Davids that challenge the Goliaths—are going to be volatile and look vulnerable at different points, even the best.

(Mary)

I agree. I agree. I’m glad that that worked out for everyone who did follow your advice.

(David)

Thank you, Marybeth. Let me ask you back: Why did you buy Palantir? Actually, let me ask you two questions really quickly. The first is, how did you even start investing? Because most people who are around your age don’t have a portfolio yet. If they do, it often isn’t with stocks. They might own funds or something else. Let’s get that start, real quick. And then why Palantir?

(Mary)

Okay, two dual-step questions. I first started investing under a custodial account when I was still a teenager in high school. This is going to sound scripted, but it’s genuinely not. I read your book The Guide to Investing for Teens. No, this is a very full-circle moment for me, very much so. I really wanted to bring my book to get it autographed, but my parents are renovating our house, so it’s in a box somewhere. But anyways, I read the book, and there were interactive activities in it. And so, I was doing that, and I was doing the math, and I was like, “You said I can make how much money?” So that’s when I really got interested in investing, listening to your podcasts. And also, my grandfather was the one who suggested looking into Palantir because he had it in his portfolio. And so that’s where I got the initial pick. And then I just did some due diligence and decided, I guess, let’s take a chance and see.

(David)

That is absolutely fantastic. Congratulations.

(Mary)

Now, I will say not every bold move pays off. Sometimes breaking the rules backfires. Can you name a time, or share a time, that breaking the rules didn’t work? And how did you reframe that failure?

(David)

Thank you. So, I could answer that. I’m just going to pick one of these two. As an entrepreneur, I have any number of stories that I could tell, but I think we’re really focusing on investing this time. So, I’ll just talk about failing in investing. And one of my favorite themes: losing to win.

A few years ago, I went back and looked at all the monthly selections I’d made for our Motley Fool Rule Breakers service. I was making two a month, every month, for a couple of decades. I counted it, and at that point, I had made 389 picks for members—some of whom had just joined a month ago, some of whom were with us all 20 years. And 389 picks—and here is a horrific fact, and it is a fact, at least it was when I calculated back then—of those, 63 of those 389 picks that people were paying me for, believing along with me that these stocks were worthy and should be in their portfolio, never thinking headstrong that we’re right, never thinking that any one company is going to take us to the moon—63 of the 389 had lost 50 percent or more of their value.

And this is me at my most mature phase, where I’ve learned all the things that I think I need to, and I’ve picked for a few decades. Sixty-three of my 389 had been cut in half or worse. And we get people who call after one bad day—they’ve just joined a Motley Fool service—stock went down 10 percent. “I don’t know what to do. Should I sell? Should I cancel the service? I’m thinking of canceling the Motley Fool service.” And it’s very understandable because people have actually… it’s heroic even to save money in this world. That’s hard to do on its own. When you actually forego the benefit, you would have gotten from that money by instead investing it, and then you watch it go down or get cut in half, that doesn’t ever—and will never—feel good. It didn’t feel good to me either.

But here’s the good news. The good news is that in that same service, of those 389 selections, the 63rd best performer was HubSpot, up 402 percent. And that was the 63rd. So, if you’re with me, and I think we’re all mathematically inclined because that’s part of physical vigor, am I right?

If you’re still with me, that means that there are 62 that had done better than plus 402. And those horrifically bad picks I made were all minus 50, 75, never even minus 100. And the top pick at the time was Tesla. It’s now Mercado Libre. It was up over 120 times in value. And on its own, that one pick actually wiped out every single one of the 63 minus-50 percenters and still left money on the table. And in between Tesla and HubSpot were 61 companies, all of which were up between five and 100 times in value.

And so, what I started to see over the course of those decades that I wanted to share in this book, and with my friends today—our friends—is that losing is overrated. You have to lose to win in this world. It’s true not just in investing, it’s true in life, it’s true in business for entrepreneurs. I think we can all look back on times that we’ve lost, and that’s part of winning. So that’s a thought about being really mediocre—or worse—and realizing when we break the rules, sometimes it hurts.

(Mary)

Yeah, I could not agree more with that. I personally—I am known for my two businesses now, but I have multiple failed ones: organic dog treats, jewelry, all of that stuff. So, I could not agree more from the entrepreneurial perspective, but also from the investing perspective. I like to diversify my portfolio using dollar-cost averaging, which is something that you talk a lot about on your platform. And my mom also likes to say, “It’s not a mistake if you learn a lesson from it.”

(David)

Beautiful. You either win or you learn. And I love that you are dollar-cost averaging. It’s a phrase I’m sure that comes trippingly to the tongue of everyone here in the audience. But for those who are just hearing it on the Catalyze podcast and are not really clear what Mary just said, this is exactly what she and I—and we all should be doing—which is, we should be regularly saving and adding, and adding and buying, and buying some more, and not worrying about whether the market is going to crash next year or whether it’s going to be a bad fall. But instead, make a whole-life commitment to investing because you should be invested your whole life. And the earlier you get started, the more time you have to compound.

Dollar-cost averaging means basically just taking that even dollar amount and putting it right back into your portfolio, your funds, your Palantir, whatever it is, every two weeks, come rain, come shine. That is such a better approach and such a less stressful approach than I think a lot of people think investing should be, where they think they have to know when the market is going to go down and what’s going to happen next.

And you really don’t ever—I don’t. But I do know, lower left to upper right over any time that matters. And so, yeah, good job on the DCA.

(Mary)

Thank you. I like to zoom out and view it on a macro level, especially because one of the greatest assets we have as current Morehead-Cain scholars is time and youth. I like to zoom out and see how the average annual return of the stock market over 100 years or something still beats inflation. But I also like to use that as an application to life as well: how when you zoom in, nothing is linear, and there’s going to be fluctuations. But when you zoom out, that positive trajectory is very encouraging and empowering.

(David)

That’s fantastic. I was reflecting with a friend recently that when I was at Carolina, even as an investor, I was much shorter-term in my thinking. And every year that I age—and I’m fifty-nine now—I actually feel like I’m longer-term in my orientation and thinking. And that really is backwards, and yet it’s really true. And I don’t know if you feel the same way, whoever you are, but I think it’s fantastic, Mary, that at a young age, you’ve achieved an ability to think big picture beyond the present day and to be running math and thinking about the long game, which is the only game worth playing.

(Mary)

So great job. Exactly. I like to also view it as a chessboard where you sometimes have to sacrifice some pieces to get that checkmate, too. You know what I’m saying?

(David)

I do, except that I never actually win.

(Mary)

Oh, well, I don’t know what to say to that. That’s not in my script. But anyway. Okay.

(David)

I mean, the only people that are still playing chess at my age are grandmasters. I mean, there are very few… It’s one of those things where people tend to hop off the wagon as they age. And the only people still playing chess at my age are really good. I’m not going to play them.

(Mary)

Okay. I accept that as a challenge. It seems these setbacks often clarify what we really value. At the Motley Fool, you call yourself the Chief Rule Breaker. How has that identity shaped both your company and your life?

(David)

Well, I think that obviously starting even before I had the phrase “rule breaker,” I was flipping through a book of quotations one night, and I was like, what are we going to call this paper newsletter for our parents’ friends? And I just settled on Act 2, Scene 7 of As You Like It, which is, I think, the greatest scene in Shakespeare. As You Like It, an incredibly great comedy, and it’s just about fools. It’s the greatest scene celebrating foolishness, going against conventional wisdom, having fun, making jokes. And I was there that night going, Oh, there’s a nondescript quote, “A fool, a fool! I see a fool in the forest—a motley fool.” And I just thought, that’s a fun place to be coming from now that I’ve lost my one job that I had up until after Carolina. At least we can tell people ahead of time, we were foolish when I pick a stock that goes down fifty percent or more. But then when you win, that’s also fun because you’ll be like, Well, those other people, they’re pretty wise. But we’re fools, and here’s what we think. So, I think even before Rulebreaker, I mean, calling yourself a fool in His Money or Soon Parted, the name that we did, given the purpose that we had, was itself rule breaking.

But then as we—when I made it forward a few years, I started realizing that how people are thinking about investing is often leading them the wrong direction. They are very frequently not buying the best companies of their time. They live and grow up with Apple, and then they come to my brother and me at a book signing or a Motley Fool event, and they’re like, I had Apple. I had it for one year. The year was 1985, and I had it. And there’s so many stories. In fact, part of not being afraid to lose fifty percent is the recognition that it’s actually when you sell out or miss something that goes up 100 times in value. Do the math—that is far, far more costly than losing fifty percent. So, I started saying, I’m going to take a different approach to investing. We might talk about it a little bit more. Thank you, Mary. One of my approaches is that I love to find stocks in the fifty-two-week high list, not the fifty-two-week low list, in order to buy that stock. And that’s in part because what do winners do in life?

(Mary)

What do winners do? Lose first?

(David)

You’re supposed to say win, but . . . but then do that. They do lose first. I really like that. But in general, it’s ironic to me that people look at a stock like Amazon or NVIDIA, and they just look at the graph over time, and yet they’re not willing to buy at that moment in the graph. This doesn’t work for Catalyze podcast, by the way. Sorry, visuals. But as that stock goes up, people become increasingly unwilling to buy it because they say, I missed it, which I would say are three of the most harmful words you could have as an investor. Anyway, so I started adopting these rule-breaker-y ways, and then it started working for me, and I started deciding, I think it’s because most other people are doing it differently. And so, to close my shaggy dog answer, I’m chief rulebreaker because, without any pun intended, I love the Davids, and in a world that is set up by Goliaths, if you follow Goliath and play the game by Goliath’s rules, you’re always going to lose—as I do at chess—because it’s Goliath. And so, you have to find a new, disruptive, think-different approach to create new value.

And of course, every one of the great companies we’ve already mentioned, and some more we will mention, have done that. They’ve broken the rules. They’ve been the Davids in their industries, and those are the companies that I love. So that’s my title.

(Mary)

And your name is very fitting as well.

(David)

I didn’t pick it. Thanks, Mom.

(Mary)

This leads me really well into my next question, which is, if you could go back to your own scholar years, what would you invest in differently? Now, this can be interpreted in very literal terms, but also on a more holistic scale.

(David)

Yeah, I think that I want to give myself credit first because I did take risks, and I do think that that is so valuable. And the younger you are, the more valuable it is to take those risks because you can bounce back. The older you get, the harder it is to take risks, and yet it’s still so fulfilling, and fellow gray hairs—still so worth doing. And of course, if you’re a rule breaker, you do that your whole life. You can’t not—not do that. But I do think that for me, thinking back on who I was and what I was doing back then, I want to say that I was taking risks. But the advice that I think I would give myself in retrospect was recognize that the world is much bigger than you think, and then, you know. And for me, coming from a small private school, Carolina was a gigantic change. And in fact, in some ways, ironically, looking backwards, I’m so glad I’m here and that I married who I did, but it wasn’t actually the right fit for me. It is a very large state university, and I was used to much smaller contexts.

(David)

I started to withdraw a little bit. I didn’t really have a great four years here because I started deciding, if you want to run the newspaper or get the lead in the play, that’s like a four-year journey. You have to work hard for four years to become editor of the DTH. I was simply not willing to do that. But I think then, as we leave Carolina, we start to realize, okay, the world is a lot bigger than Carolina. And you start to just sense the incredible scale and then the history that’s led and the goodness that’s led to the scale that we take for granted sometimes today. So maybe also something to be said for taking more history classes, which I didn’t have as much appreciation of at the time. But I would also give myself advice like, sell AOL in 2001. Buy any great stock even earlier. Those are jokes too easy to make, though. Thank you.

(Mary)

Totally got you. I would be taking notes right now, but unfortunately, I’m moderating this conversation.

(David)

And by the way, this is Mary moderating for the first time, she told me, and what a fantastic job she’s doing. You are used to answering questions. You’re used to performing. You said to me just in the green room, just before we came on, and you also said, this is a great opportunity for you to grow because now you can see what it’s like from the other side. And isn’t that a constant intellectual curiosity, growth mentality? Love it. Thank you.

(Mary)

You’re welcome. I really appreciate that. Yes, usually I’m on the other side, but I was so excited for this opportunity to talk to you, so I’m here. Let’s now move on towards some financial advice, which is what I know everyone came here to hear. You’ve just released a new book, Rule-Breaking Investing, last month, actually. The book outlines six habits, six stock traits, and six portfolio principles. Unfortunately, we can’t cover all eighteen right now, but I was hoping you could give your top three of each.

(David)

Thank you. I’m going to give my top one of each because if I give them a top three, we’ll be giving me the hook. I will say, though, Mary, thank you. I’m going to give my favorite habit, my favorite trait, and my favorite principle. And thank you for outlining how the book is laid out. Because we start with the six habits, because we could talk stocks, which we’re about to. But if we’re not actually doing it right in the first place, if we say Apple and then somebody doesn’t hold Apple, it doesn’t really matter that we said Apple. It’s really about where we are and what our mindset is. And then the stocks. And then if you’re doing habits and stocks, and I like stocks, we can talk funds, too. I love stocks. But if you’re doing those two things, you end up with a portfolio. And here again, most people don’t necessarily have coaching or thinking around how to run a portfolio. The most frequent question I get on my Rule-Breaker Investing podcast is, how many stocks should I have in my portfolio? Which is a very understandable question. It’s also not the right question.

There’s no one answer to that. So, let’s do a flyby. In fact, I was realizing this the other day. I have six habits, six traits, six principles. That’s eighteen. This is like Augusta. It’s the Masters. We’re doing the drone flyby of eighteen—not holes, but things. We’re just going to touch one, seven, and thirteen. So, one is habit number one. And habit number one of the Rule-Breaker investor is rule number one: let your winners run high. And I think you’ve already heard some from me about that. And I’ll add to it that you’re only ever going to get a 100-bagger, or a stock that goes up 100 times in value, which I hope Palantir eventually does for you, if you’re willing to allow it to do that. It’s amazing how many people had Amazon for a little while or had this or that. And then they got scared out. Maybe some person talking on TV, telling them to sell one night, or maybe they just, by nature, worry about staying involved in the market when it goes down. The stock market goes down two years out of every three. It goes… Sorry, the stock market goes up two years out of every three; otherwise, it wouldn’t be here.

It goes down one year out of every three. And those are hardwired numbers over the last century. So that means if you’re invested for your whole life, which you are, Mary, you’re going to have about thirty years or so of the stock market going down. And if you try to jump out before that or guess when that’s going to be, I think you’re really going to mess yourself up. So, I’ve ridden the roller coaster all the way up and all the way down constantly. Rule number one: let your winners run high. And when you do, when you truly allow excellence to become excellent, it is so fulfilling, satisfying, and enriching. My first trait, my favorite trait for Rule-Breaker stocks, is top dogs and first movers in important emerging industries. So real quick, the second part of that phrase—important emerging industries—let’s light upon that briefly. The great companies, the great stocks come not because we’re buying Coca-Cola now in its second century of operations, but because we found an important emerging industry of technology, and they are burgeoning. I had the great fortune. Those around the class of ‘88, ‘89, ‘86, shout out to us.

The Internet showed up just a couple of years after I graduated. That was an amazing plate tectonic shift. I had nothing to do with it, and I absolutely love that it did. It’s added so much value to our society and our lives. There are negatives around it, too, but net, net, huge benefit. The same will be true of AI. AI is not an industry. It is a technology. It is a plate tectonic shift. And just as Uber and Airbnb showed up fifteen years after the Internet started, there will be amazing AI companies that don’t exist yet now, that ten years from now you’ll be watching. I will, too, because whole industries are spawned by plate tectonic shifts. So important emerging industries. And then top dogs and first movers. I want to find the company that is led by the visionary who got things started. And more often than not, when it works, it works so wonderfully. Jeff Bezos. People have mixed feelings about him these days. Elon Musk. Reed Hastings. Steve Jobs. The list goes on. Lisa Su. Entrepreneurs who are basically driving ridiculous amounts of scaled value that I could never have understood at my small private school or even my large public university—a scale that extends across our world.

And these are the companies and the people that I want to be invested in. So top dogs and first movers. There’s a great line about—I guess it’s the Iditarod— “If you’re not the lead husky, the view never changes.” And I agree. I only want to have the lead huskies in my portfolio. And if you fish in a pond that’s stocked with only the top dogs and first movers across every industry—the innovators in every industry—and just fish in that pond with your little fishing pole in mind, too, we are finding and fishing the great companies. And it’s amazing how few people are around that pool because they either are scared of new technologies or they’ve heard they should never buy Amazon because it’ll never make money.

(Mary)

I have a question. How do you identify these and keep these on your radar?

(David)

With a little help from my friends. How did I find Palantir? How did you find Palantir? From friends, right? We’re such social creatures. And part of the reason I love this forum and come back every single time—except I missed one—is you. You. You people that I meet, old friends I get to see again, new friends that I meet each time. We benefit so much from spending time with bright people. The best people in the room that I can find in any given room have enriched my life so wildly. So yes. And I realized time is going to start running out. Mary, I should throw down my first principle of the Rule-Breaker portfolio really quick, and that is to make your portfolio reflect your best vision for our future. And I really truly believe that if every one of us is one-to-one with what we believe in this world, what we hope for, and we actually get our money deployed there—not only is it going to be much more fulfilling as that happens, but you’re actually going to do a lot better than if you listen to somebody else who’s giving you advice about funds or this or that thing, and you’re not really sure what that is, but it’s your money.

(David)

I think if you make your portfolio reflect your best vision for our future, we all see different parts of the elephant, so we’re each going to have different portfolios. That’s portfolio principle number one.

(Mary)

I love all your metaphors. I just want to give you a shout-out for that. Thanks. And so, it seems like if there’s one thing we can walk away with today, it’s this: breaking rules isn’t about reckless speculation, but about creating long-term value. David, you’ve given us a priceless return on investment this afternoon. I have one last question. What is your secret to success?

(David)

Thank you for asking a question, Mary, that I set you up to ask me. First of all, I want to thank you for that, because not every moderator would be so generous. I told Mary, because we did a pre-interview, and she prepared great questions. She brought everything today. And I said, Mary, at the end, I have a line that makes people laugh every time. So, if you want, you don’t have to, but you could ask me what my two secrets to success are. And she just did that. Is this it? After I say this, are we done?

(Mary)

Get up and go. I have a little closing. Okay, good.

(David)

I apologize that I’m going to make your closing anticlimactic because of how funny my closing line is. And I’ve had more heads who’ve come up to me because I’ve done this before, and they’re like, I use that one, too, now. And so here it is, a gift to us all. Mary, what did you want to hear from me?

(Mary)

I wanted to know, what is your secret to success?

(David)

Did you mean my two secrets to success?

(Mary)

Your two secrets to success. Guys, I’m really nervous.

(David)

Number one: never tell everything you know. Thank you. It works every time. I realized some of you were fake laughing just to make me feel good.

(Mary)

David, thank you so much. And thank you to our first live audience. You all have been wonderful. And remember, none of this is financial advice, so you can’t sue either of us if you make a foolish move. But it is life advice, and who better to receive it from than David Gardner, co-founder of the Motley Fool and Morehead-Cain Class of 1988. Thank you for listening to Catalyze. I’m Mary Esposito from the Class of 2026, and that was David Gardner from the Class of 1988. You can let us know what you thought of this episode by following us on social media at Morehead-Cain or by emailing us at communications@moreheadcain.org. Please, one more round of applause for David.

(David)

Thank you.